La plasticité conceptuelle du mot “Yoga” soulève une question fondamentale : comment comprendre l'unité profonde du Yoga au-delà de ses manifestations historiques si diverses ? Existe-t-il un "fil rouge" permettant de saisir la cohérence de cette tradition millénaire, depuis les hymnes védiques jusqu'aux pratiques contemporaines ?

Pour répondre à cette interrogation, il faut remonter aux sources de la civilisation indienne et suivre pas à pas les transformations du concept yogique. De l'ordre cosmique védique à l'individualisme des Renonçants, de la tentative de synthèse sociale du

Bhagavad-Gītā, des raffinements techniques du Haṭha-yoga, à l’inconcevable du Rāja-yoga, chaque période a apporté sa contribution à l'édifice complexe que nous appelons aujourd'hui "Yoga".

Des Vedas aux Upaniṣad : l'émergence du Yoga Le Yoga est présenté par Tara Michaël

[1] comme l'épanouissement naturel de la civilisation indo-aryenne védique. Cela veut dire que les concepts fondamentaux, les pratiques et les objectifs ultimes du Yoga seraient profondément enracinés dans la tradition védique, et se seraient développés de manière organique à partir d'elle, plutôt que d'être une importation ou une création tardive isolée. Le concept de Yoga prend une importance significative et une forme plus explicite avec la fin des Veda (Vedānta), c'est-à-dire les Upaniṣad. Les Upaniṣad explorent en effet la doctrine de l'identité de l'ātman (le Soi individuel) avec Brahman (le Principe suprême), comme en témoignent les "grandes paroles" (

mahāvākya) telles que "

Tat tvam asi" ("Cela, tu l'es !").

Le mot "Yoga" vient de la racine sanskrite

yuj, qui signifie "atteler ensemble, joindre, unir". Il s’agirait de l'union de l'être individuel (

jīvātman) au Principe suprême (

Paramātman)

[2]. C'est l'objectif ultime, la réalisation de l'identité du moi avec le Divin. Il ne faut pas perdre de vue que les discours et les méthodes du“Yoga” ont évolué, et qu’en regardant en arrière, la tendance existe d’interpréter les formes anciennes du “Yoga” à la lumière des plus récentes.

L’objectif des Vedas n’était pas de joindre l'être individuel au Principe suprême. L'objectif principal des Veda était de maintenir l'ordre cosmique (

Ṛta), avec ses varṇa

[3], et de s'assurer la prospérité par des rites et sacrifices extérieurs (

yajña) offerts aux divinités, dans le but d'obtenir des bienfaits terrestres ou célestes. Dans la conception védique primitive, la mort n'implique pas de réincarnation. Les trépassés retrouvent leurs ancêtres, leurs Pères (

pitṛ), et accèdent au mondes célestes et lumineux des

deva. Le destin post-mortem suit deux voies principales : soit le combattant mort prend la direction du nord, celle des dieux (

devayāna), soit la direction du sud

[4], celle des mânes (

pitṛyāna). Il n’y a pas encore l’idée du retour du cycle de naissances, et d’une sortie (

mokṣa) de celui-ci.

Le passage du ritualisme védique à la quête individuelle de salut (

mokṣa) dans les Upaniṣad s’explique par une évolution sociale, intellectuelle et spirituelle profonde, marquée par la remise en question du rituel extérieur, l’essor de l’ascétisme (pratique individuelle), l’influence de courants contestataires, ainsi que la valorisation de la connaissance de soi comme voie de libération.

Last but not least, les

kṣatriyas (“aristocrates”), traditionnellement en rivalité avec les brahmanes (prêtres), ont pu voir dans la philosophie des Upaniṣad un moyen d’affirmer leur propre légitimité spirituelle, en contestant la suprématie rituelle des prêtres et en revendiquant un accès direct à la connaissance suprême. Dans la

Chandogya Upaniṣad (VIème AEC) et la

Brihadaranyaka Upaniṣad (VIII-VIIème AEC), des rois enseignent à des brahmanes, illustrant une inversion des rôles et une volonté de puissance symbolique de la part de l’aristocratie.

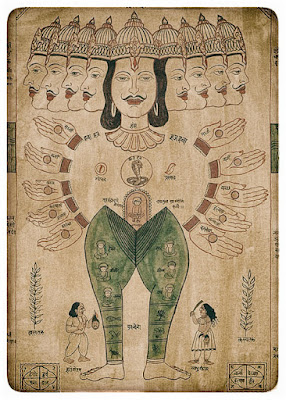

|

| Virāṭ Puruṣa, manuscrit Bhāva Prakāśa (XVIe siècle) |

L'individualisation du salut avec les Renonçants L’objectif devient, dans “le Yoga”, la libération individuelle (

mokṣa), c’est-à-dire la délivrance du cycle des renaissances (

saṃsāra) par la réalisation de l’unité entre l’âme individuelle (ātman) et le principe absolu (

brahman). Les grands fondateurs des mouvements de “Renonçants” (

śramaṇa), ou leurs disciples, venaient de l’aristocratie. Siddhārtha Gautama (bouddhisme), Mahāvīra (jaïnisme), Makkhali Gośāla (Ājīvika), etc. enseignaient un salut individuel, plus ascétique, plus “héroïque”. On trouve le même individualisme chez les yogis, adeptes des Upaniṣad.

Les Renonçants font figure de “

self-made men”, qui semblent tourner le dos aux services religieux de la caste des prêtres brahmanes, qui sont d’ailleurs souvent

la cible de moqueries. Leur objectif ne sont pas les bienfaits terrestres ou célestes, mais le nirvāṇa, la sortie définitive du cycle des renaissance. Le Bouddha pāli ne cherchait pas “l’union” (

yoga) avec le Principe suprême. Le nirvāṇa n’est pas une union, mais une “extinction”. Dans la civilisation indienne, une flamme soufflée, n’est

pas le néant[5]. La méthode bouddhiste pāli ne visait pas

l’union, ou l’identification. Ni une Connaissance directe (

jñāna) ou Gnose. L'union de l'être individuel (

jīvātman) au Principe suprême (

Paramātman) requiert la libération individuelle (

mokṣa) ET une “Connaissance directe” (

jñāna), qui le conduit ou accueille dans un “Ailleurs” qui est au fond le vrai “Chez Soi”. La sortie du saṃsāra, suffisait, et était justement le nirvāṇa. Un Yoga dans le sens d'union de l'être individuel (

jīvātman) au Principe suprême était superflu. Ni l’être individuel (

ātman) ni l’Être suprême n'étaient étaient des facteurs à prendre en compte. La libération semble donc possible avec ou sans union de l’être individuel et de l’être suprême.

Le Bhagavad-Gītā : vers un Yoga sociétal

Le

Bhagavad-Gītā est une œuvre majeure qui, bien que faisant partie de l'épopée du

Mahābhārata, est généralement datée entre 500 avant et 500 après J.-C., et en constante évolution. La première mention claire et systématique des six

darśana (écoles de pensée) date des premiers siècles de notre ère (IIᵉ–Vᵉ siècle), même si les écoles elles-mêmes sont plus anciennes et que la tradition doxographique s’est consolidée au fil du temps. Le

Bhagavad-Gītā donne une place importante au Sāṃkhya, qui propose une analyse rationnellement de la réalité. Il reprendra la distinction

puruṣa/

prakṛti (Esprit/Nature) du Sāṃkhya, mais l’oriente vers la réalisation de l’

ātman et l’union avec le divin. Le

Bhagavad-Gītā valorise le Yoga comme discipline de l’esprit, mais l’intègre à la dévotion (

bhakti) et à l’action désintéressée (

niṣkāma-karma). Il propose un triple Yoga, adapté à chacune des quatre

varṇa (castes).

Le Karma-yoga (Yoga de l'action), qui vise à purifier la volonté. Ce type de yoga met l'accent sur l'action désintéressée, en réalisant les actes prescrits sans attachement à leurs résultats, car "l'action est supérieure à l'inaction ; même ta vie physique ne saurait se maintenir sans action".

Le Bhakti-yoga (Yoga de l'amour ou de la dévotion), qui purifie le sentiment et est décrit comme "la voie dans laquelle un amour intense permet au yogin de s'élancer jusqu'à la Réalité Ultime et de s'en emparer". Cette voie est ouverte à tous, sans restriction. Elle démocratise le salut.

Le Jñāna-yoga (Yoga de la Connaissance), qui purifie l'intellect, mais dans le but de préparer son dépassement en vue de l’union avec l’Être supreme. Il faut par exemple faire la distinction entre

la lucidité (prajñā, apophatique, négative), et la

“Connaissance”, que je traduis souvent par Gnose (

jñāna, positive).

Le

Bhagavad-Gītā démocratise le Yoga, et instaure une sorte de “contrat social”, où chacun peut devenir “Yogin”, à condition d'accomplir son

svadharma (devoir propre à chacun, y compris selon sa caste). La recherche du salut individuel peut (re)faire société ?

« Mieux vaut accomplir son propre devoir, même imparfaitement, que d’accomplir parfaitement le devoir d’autrui » (Bhagavad-Gītā III.35).

« Celui qui, sans attachement, accomplit l’action qui doit être faite, celui-là est un yogin » (Bhagavad-Gītā VI.1).

“Nous avons déjà attiré l'attention sur le succès qu'a remporté le message de la Bhagavad Gītā jusqu'à nos jours. Nous ne saurions qu'admirer l'habileté avec laquelle les brahmanes parvinrent à faire d'une force qui poussait à quitter la société l'un des piliers d'une société conçue sur le modèle brahmanique.” (Bronkhorst, 2008[6])

Patañjali et le “Rāja-yoga” : la voie royale de la maîtrise mentale Les

Yoga-sūtras de Patañjali (entre le IIe siècle avant notre ère et le Ve siècle après notre ère) proposent une voie plus élitiste et plus individuelle, sous la forme d’un Yoga “supérieur”, le “Yoga royal” (

Rāja Yoga) à huit branches (

aṣṭāṅga-yoga), que l’on retrouvera (en partie) jusqu’à dans les yogas supérieurs du bouddhisme tibétain. Ils visent la maîtrise du mental et la réalisation de la nature véritable du Soi, par la méditation et la discipline intérieure, et non par le rituel, la dévotion ou la spéculation intellectuelle seules.

Le retour brahmanique : Yājñavalkya et le Yoga sacrificiel Un nouveau tournant avec le

Yoga-Yājñavalkya-Saṃhitā, un traité sur le Yoga (200-400 AD), attribué à un certain Yājñavalkya, qui n’est pas celui du

Bṛhad-Āraṇyaka Upaniṣad. Ce texte, ainsi que le Yoga-Vasiṣṭha attribué à Vasiṣṭha, présentent un "Yoga brahmanique" destiné aux

muṇi, des sages mariés et maîtres de maison, et se distingue du Yoga formulé par Patañjali en ce qu'il n'exige pas un renoncement impératif à toute action, qu'elle soit rituelle ou mondaine, ni un détachement de tous les liens affectifs, familiaux et sociaux. Le Yoga qu'il caractérise met l'accent sur la pratique combinée des rites védiques (l'« Action » sacrificielle) et des disciplines du Yoga. Ces précurseurs n'enjoignent pas la cessation de l'action, mais plutôt son accomplissement sans désir de bénéfice personnel. Tara Michaël appelle cette tendance yoguique le “

Yājña-yoga” (Yoga sacrificielle).

Une voie de libération pour classes moyennes : un Yoga sans renoncement Il n’est pas exclu que le

Yoga-Vasiṣṭha s’est très largement inspiré du

Mokṣopāya (MU), aurait été composé autour de 950 au Cachemire dans des milieux aristocrates (

kṣatriya), et serait

une sagesse destinée au rois (rājavidyā), ou sinon à des individus actifs (

gr̥hastha, gahapati) dans la société, leur permettant d’atteindre le statut de libéré-vivant (

jīvanmukti).

“Ces sages védiques, experts en rites, n'interrompaient à aucun prix leur activité sacerdotale, même dans le troisième stade de leur existence, celui où l'on prend un recul, dans de calmes et accueillants ermitages forestiers, tout en réfléchissant sur la signification intérieure du sacrifice.

Leur Yoga se caractérise par une insistance sur la pratique combinée des rites védiques (ce qui est appelé “ l'Action “, l'action sacrificielle étant l'action par excellence) et des disciplines du Yoga censées engendrer la Connaissance suprême (ce qui est appelé “la Connaissance née du Yoga, ou la Connaissance ayant le Yoga pour essence”.” (Michaël, 1992)

On n’échappe pas à l’idée d’une religion sur mesure et au service des classes supérieures. Le brassage des castes et de sexes traditionnellement associé au tantrisme est en grande partie un mythe. Quelque part le tantrisme c’est le statut du brahmane mis à la portée de certains élites non-brahmanes.

Ces phénomènes de « brahmanisation »,

notamment dans le Yogācāra (qui signifie "la pratique du Yoga") et

le bouddhisme ésotérique, qui en était le prolongement (David MacMahan), ne se limitaient d’ailleurs pas à l’Inde. Noubchen Sangyé yéshé (T.

gNubs chen sangs rgyas ye shes, 10ème siècle) est l’auteur de la «

Lampe éclairant l’œil de la méditation » (T.

bsam gtan mig sgron), un recensement des quatre approches de méditation utilisées au Tibet à l’époque. Il y donne une liste de quatre choses favorables dont un homme de religion devrait disposer :

1. Un compagnon expérimenté (T. nyams dang ldan pa’i grogs) dans le cas où il est difficile de trouver un maître capable d’intervenir en tant que maître qualifié.

2. Un partenaire féminin (mudrā) qualifié qui a toutes les caractéristiques physiques et spirituelles nécessaires (T. mtshan dang ldan pa’i phyag rgya), dans le cas d’un adepte des tantras Mahāyoga.

3. Une bibliothèque avec les textes recommandés (T. bsam pa dang mthun pa’i dharma)[5].

4. Un serviteur agréable (T. yid du ’ong ba’i g.yog)[7].

Il y a une certaine aisance et conscience de statut social qui se dégage de tout ça…” (Blog

La recherche de l’éternel féminin au détriment de la femme 2011.

Sans Dieu, point de Yoga : la dimension théologique irréductible Le fil rouge du Yoga est l'union de l'être individuel (

jīvātman) au Principe suprême (

Paramātman). C’est un système théologique, quelle que soit la définition de l’âme d’un côté et de l’Être suprême, ou de l’Īśvara, de l’autre. Le Yoga post-védique a un double objectif, la sortie du

saṃsāra et l’union à l’Être suprême, ce dernier comprend automatiquement le premier. Au temps des

śramaṇa, le détachement et le renoncement étaient considérés comme une étape nécessaire à cette union, d’où la vocation de nombreux Renonçants (

śramaṇa). Parmi ces Renonçants, il y a avait ceux qui admettaient un Être suprême et une âme individuelle, et dont l’union était l’objectif ultime, et ceux qui ne cherchaient que la sortie du

saṃsāra. Il faut distinguer ces chercheurs “

nāstika” (“

non-théistes”) des

Cārvākas “matérialistes”.

Le “Dieu”, auquel il faut s’unifier peut être un Principe suprême (Brahman), “appelé tel dans son essence impersonnelle, sans spécifications ni attributs (

nirguṇa)”, mais plus souvent une “Personne suprême” (

parama-puruṣa), “dotés des attributs divins (

saguna) tels qu’omniscience, omniprésence, omnipotence, etc., qui font de lui “le Seigneur” de l’univers et des âmes (

Īśvara), Dieu.” (Michaël, 1992, p. 37).

Cette distinction n'est pas anodine : elle reflète la polarité fondamentale entre les voies yogiques. Ainsi, le grand maître du Jñāna-yoga, Śaṅkara (VIIIe siècle), visait l'union avec le Brahman

nirguṇa, l'Absolu sans attributs, tandis que les adeptes du Yoga sacrificiel (

Yājña-yoga) et dévotionnel prennent pour objet de vénération une Personne suprême (

Īśvara) dotée d'attributs divins. On pourrait faire un parallèle entre néoplatoniciens “théologiques” (Plotin, etc.) et les

néoplatoniciens “théurgiques” (Proclus, Porphyre, Iamblichus, etc.).

Déceler les constantes : polarités et synthèses du Yoga Contrairement à la société védique sacrificielle, le projet du Yoga est individuel. Le salut de tout un chacun est une affaire individuelle, ascétique, extérieure et/ou intérieure (p.e.

Haṭha-yoga). Une évolution va rarement dans un sens, et les allers-retours sont possibles, y compris néo-védiques. Le

Bhagavad-Gītā propose un Yoga collectif, sociétal, ou chacun selon ses dispositions individuelles, sociales, peut trouver la voie du Yoga qui lui correspond :

devoir sociétal (Karma-yoga, svadharma), ferveur dévotionnelle (

Bhakti-yoga) et Gnose (

Jñāna-yoga).

Le devoir sociétal (

svadharma) prend la place de l’ancienne action rituelle (

karma), mais la véritable action rituelle fera un retour dans ce que Tara Michaël appelle le "Yoga sacrificiel" (

Yājña-yoga) de Yājñavalkya et de Vasiṣṭha, et qu’on pourrait appeler néo-védique, un retour vers la société sacrificielle. Tout le long de l'histoire post-védique de la culture indienne, on voit des va-et-vient entre les deux pôles sacrifices (

karma) et Gnose (

jñāna).

Ces deux pôles trouvent un certain consensus en des formes “sacrificielles” (

karma) intériorisées, dont une des formes les plus connues est le “

Haṭha-yoga”. Pour les adeptes du “Yoga royal” (

Rāja-yoga), le Haṭha-yoga “énergique” est une préparation au Rāja-yoga “royal”. Le Raja-yoga est une "discipline purement mentale", visant le "contrôle des activités de l'esprit" (

citta-vṛtti-nirodha) et aboutissant au

Samādhi, qui est considéré comme l'essence même du Yoga ("

Le Yoga, c'est le samādhi" Vyāsa). Cette emphase sur le psychisme et l'absorption spirituelle distingue le Rāja-yoga des autres voies axées sur l'action (sacrificielle ou sociétale), la dévotion ou l’énergie. Dans le schéma ci-dessous, on peut voir comment Tara Michaël représente la nouvelle situation des différentes voies de Yoga. La tension originelle Karma-Jñāna existe toujours, mais sous les formes du Yājña-yoga et du Rāja-yoga (noms ultérieurs). La voie dévotionnelle est présentée comme une troisième voie à part, “démocratique”, ou sinon du moins identitaire. L’objectif ultime du Yoga, selon sa propre définition, est double : l’union à Dieu et/ou la libération.

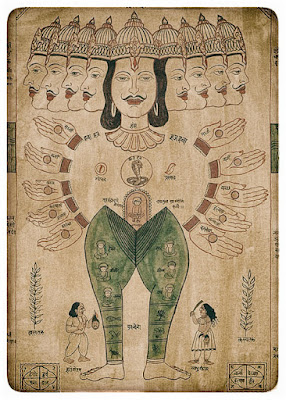

|

| Schéma Tara Michaël, dans Le Yoga de l'éveil |

Dans le tantrisme (y compris bouddhiste), toutes ces voies ou filières différentes du Yoga sont amalgamées, et centrées sur une Divinité avec sa sphère (

maṇḍala). La libération (

mokṣa) ne suffit plus dans le bouddhisme ésotérique, il faut une “

réalisation lumineuse”. La libération est bon pour le

dharmakāya du Bouddha, mais le

saṃbhogakāya et le

nirmāṇakāya requièrent

une union/réalisation topique (topos) et gnostique, que l’on peut appeler lumineuse ou divine, et qui est assez similaire à l’union Shivaïte “

sāyujya”

[8]. La "vacuité" n'y change pas grand chose...

Les virtuoses du non-mental : au-delà de toute technique Dans “

Le yoga de l’éveil dans la tradition hindoue”, Tara Michaël publie la traduction française de l’

Amanaskayoga (

Amanaska-yoga-śastra[9]), un dialogue entre Īśvara (Śiva) et Vāmadeva (un

deva), attribué à Gorakṣanātha

[10], le fondateur de l'ordre des

Nātha-yogin, traditionnellement associé au Haṭha-yoga. Ce yoga non-conceptuel ou non-mental (

amanaska), est considéré comme la dernière étape du Rāja-yoga. L'

Amanaska se distingue par son rejet de la plupart des techniques du Haṭhayoga et d'une approche "sans effort" vers la libération. Il critique explicitement les auxiliaires du yoga (comme les

yama/niyama,

āsana,

prāṇāyāma), la métaphysique complexe, les mantras, l'ascétisme brahmanique et non-brahmanique, ainsi que les pratiques des

Kāpālikas, les jugeant inutiles ou même nuisibles. Il prône une pratique simple centrée sur la

Śāmbhavī Mudrā et le

Samādhi (

amanaska) (Birch, 2013). Dans la

Śāmbhavī Mudrā, les yeux sont à demi ouverts, le mental est stable, et le regard est fixé sur le bout du nez. Jason Birch met en lumière que la relation entre le Rājayoga et les

Yogasūtras est un développement tardif du XIXe siècle. L'

Amanaska (XIe ou début du XIIe siècle de notre ère) est l'un des premiers textes de yoga à utiliser le terme Rājayoga et le plus ancien texte existant à le définir.

L'

Amanaska se divise en deux parties, initialement composés comme des œuvres distinctes par des auteurs différents, et combinés à un stade ultérieur (Birch, 2013). Deux pratiques,

avec mental (

Tāraka) et

sans mental (

Amanaska[11]). Le

Tāraka-yoga est un yoga préliminaire (

pūrvayoga) où l'on fixe les yeux sur une lumière

[12] et l'on lève légèrement les sourcils. Cette pratique est censée "spontanément" provoquer l'état non-mental. l’

Amanaska rejette explicitement les pratiques impliquant un support de méditation ou des objets de concentration, arguant que le véritable état de non-mental (

cittādi-laya) ne nécessite pas d'objet. Il se positionne en opposition aux systèmes de yoga gradualistes (comme le Haṭha-yoga ou le Ṣaḍaṅgayoga) qui s'appuient sur des techniques et des supports externes ou internes. L’

Amanaska considère que de telles méditations, bien qu'utiles pour préparer le mental des "

hommes dont l’intellect se laisse duper par l’illusion", sont des constructions mentales et ne représentent pas la réalité ultime.

L'

Amanaska affirme que le Prāṇāyāma et, par extension, d'autres techniques de méditation avec support, sont un effet du Samādhi et non sa cause. Le but est d'atteindre l'état d'

amanaska (non-mental), qui est synonyme du Samādhi et de l'état ultime de Rāja-yoga, un état de non-agitation mentale totale, de "

pure existence sans manière d’être" (Silburn, 1999

[13]). Cet état est intrinsèquement "

naturel" (

sahaja). C’est la traduction utilisée par Jason Birch (2013).

Verset 91 “Ainsi a été enseigné cet état naturel de non-mental (sahajāmanaskaṃ) pour l'éveil des disciples, directement par Śiva. Cependant, [cet état de non-mental] est éternel, sans aspects, indifférencié, non exprimable par la parole et ne peut être expérimenté que par soi-même seul

Verset 92 “Lorsque le mental est en mouvement, le cycle des renaissances prévaut. Lorsque [le mental] est immobile, la libération surgit. C'est pourquoi [le yogin] doit stabiliser son mental ; il est voué à [la pratique du] détachement complet.[14]”

La singularité de la doctrine de l'

Amanaska est de rejeter les méthodes physiques et cognitives conventionnelles du Yoga en faveur d'un état de non-mental obtenu par l'abandon de l'effort et la dissolution spontanée de l'esprit, sous la guidance du guru, menant à une réalité au-delà de toute description et de toute limitation corporelle.

Verset 108 “La maîtrise du souffle peut être obtenue par les trois types d'Om et par diverses Mudrās [haṭha-yogiques], ainsi que par la méditation sur une lumière ardente (tejaścintanam) [ou la méditation] sur un objet de support tel que le ciel vide, [ces pratiques] étant réalisées dans le lotus de l'espace intérieur [du cœur (antarālakamale)]. Cependant, considérant tout cela, situé dans le corps, comme une illusion du mental, les sages devraient pratiquer l'état de non-mental (amanaskatva), qui est unique, au-delà du corps (dehātītam) et indescriptible (avācyam).[15]”

Conclusion

À notre époque, où l'attention devient le bien le plus précieux, seuls des yogins experts peuvent se permettre de consacrer leur temps au “Yoga sacrificiel”, ou toute leur attention au “Yoga de Connaissance" (non-mental). Pour le commun des mortels, la voie de la dévotion et la voie "du devoir sociétal" (

svadharma) sont plus probables, pour réussir "l'union de l'être individuel (

jīvātman) au Principe suprême (

Paramātman)", autrement dit le “Yoga”.

Mais cette observation soulève une question fondamentale que l'histoire du Yoga éclaire cruellement : peut-on encore se satisfaire d'un salut essentiellement individuel dans un monde où les défis collectifs et climatiques deviennent incontournables ? Si les défis collectifs ont toujours existé, l'affaiblissement de l'horizon religieux universel transforme radicalement la donne. Quand la promesse d'un Au-delà divin légitimait le détachement du monde terrestre, l'indifférence aux injustices sociales pouvait se justifier par la perspective du salut éternel qui le sublimait. Mais que reste-t-il de cette logique quand l'impact religieux s'estompe ?

Le “Yoga” moderne (et au fond la spiritualité en général), qu'il prenne la forme du

wellness occidental ou du

mindfulness corporate, fonctionne largement comme un mécanisme de dépolitisation. Plutôt que de questionner les structures qui génèrent stress et inégalités, il propose des solutions individuelles d'adaptation. En cela, il reproduit la logique du

svadharma antique : chacun à sa place, chacun responsable de son propre salut (

Yoga).

Pourtant, l'histoire même du Yoga révèle sa remarquable plasticité conceptuelle. Si la tradition a toujours supporté de grands écarts théoriques et pratiques - du ritualisme védique au renoncement ascétique, de l'élitisme de Patañjali à la "démocratisation" de la

Bhagavad-Gītā - c'est que son fil rouge (l'union de l'être individuel au Principe suprême) reste suffisamment abstrait pour autoriser les réinterprétations les plus diverses. Le collectif (≃

viśvarūpa) ne se situe-t-il pas entre l’individuel et le Suprême ? Cette plasticité qui a permis tant de récupérations pourrait-elle aujourd'hui servir une transformation émancipatrice ?

Imaginer un "karma-yoga" qui ne se contente pas d'accomplir pieusement son devoir social, mais qui œuvre activement à transformer les structures d'oppression. Concevoir une "union divine" qui passe par la solidarité concrète plutôt que par l'évasion mystique.

L'enjeu n'est plus de démocratiser l'accès à une spiritualité méritocratique, mais de réinventer une pratique de libération qui soit à la fois personnelle et politique, contemplative et engagée. Cela supposerait d'abandonner le modèle traditionnel de l'ascension individuelle méritoire - où chacun gravit péniblement l'échelle spirituelle selon ses efforts et ses dispositions - pour concevoir une "union divine descendante" qui irrigue le collectif.

Cette intuition trouve un écho saisissant dans la tradition bouddhiste avec

Śāntideva, qui propose de considérer tous les êtres "comme des parties de l'univers", à l'image des "mains qui protègent le pied" dans un seul corps. Au lieu de chercher son salut individuel, le bodhisattva étend sa notion de "soi" jusqu'à englober tous les êtres souffrants : "Pourquoi ne pas considérer les corps des autres comme 'moi' ?" Cette révolution conceptuelle transforme la libération d'un projet d'évasion personnelle en responsabilité collective.

Plutôt que de chercher à s'élever vers l'Absolu par des pratiques d'élite, avec des missions allers-retours vers la Terre, il s'agirait faire émerger une grâce humaine à portée de tous les humains, qui se diffuse horizontalement, créant des liens de solidarité plutôt que des hiérarchies de réalisation ascensionnelle. Cette inversion théologique aurait des implications politiques majeures : elle transformerait le Yoga d'un instrument de distinction spirituelle, et par là sociale… , en force de transformation collective.

Imaginer aujourd'hui un karma-yoga qui ne se contente pas d'accomplir son rôle individuel, mais qui œuvre activement à transformer les structures d'oppression. Concevoir une bhakti qui ne fuit pas le monde dans la dévotion privée, mais qui reconnaît le divin dans les opprimés, et l’activité divine dans la solidarité concrète avec les opprimés. Retrouver un jñāna-yoga qui ne soit pas accumulation d'expériences spirituelles personnelles, mais la conscience que "ma" libération passe nécessairement par celle de tous. Surtout si l'on est un bodhisattva.

***

[1] Tara Michaël,

Introduction aux voies du Yoga, Desclée de Brouwer, 2017

“

Les origines proprement dites du Yoga se perdent dans la nuit des temps. Celui-ci représente, semble-t-il, l’épanouissement naturel de la civilisation indo-aryenne védique.”

Autre source pour ce blog : Tara Michaël,

Le Yoga de l'Eveil dans la tradition hindoue, 1992, Fayard.

[2] Yājñavalkya, un adepte du Yoga à ne pas confondre avec l'adepte révéré du

Bṛhad-Āraṇyaka Upaniṣad (datant du VIIIe siècle av. J.-C.), est crédité d'avoir formulé la définition du Yoga comme "

l'union du jīvātman avec le paramātman" (

samyogo yoga ity ukto jivatmaparamatmanoh). Cette citation spécifique provient du

Yoga-Yājñavalkya-Saṃhitā (YYS I.43). Voir Whicher, Ian,

The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana : A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga, 1998, SUNY.

Le

Yoga-Yājñavalkya-Saṃhitā est un traité sur le Yoga attribué à

Yājñavalkya. P. C. Divanji ("

Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society") suggère que ce texte pourrait dater de 200 à 400 de notre ère. Cependant, Feuerstein estime que c'est une œuvre plus tardive, possiblement du XIIe siècle de notre ère, ou même plus tard.

[3] La société védique se structure déjà en quatre grandes divisions (

varṇa) : les brahmanes (prêtres), les kshatriya (guerriers), les vaishya (paysans et commerçants) et les shudra (serviteurs). Cette organisation, qui préfigure le système des castes, trouve sa justification théologique dans le célèbre hymne du

Puruṣasūktam : "

Sa bouche devint le brahmane, le guerrier fut le produit de ses bras, ses cuisses furent l'artisan, de ses pieds naquit le serviteur"

“

brāhmaṇo'sya mukhamāsīd bāhū rājanyaḥ kṛtaḥ

ūrū tadasya yad vaiśyaḥ padbhyāṃ śūdro ajāyata” (Rig-Veda X.90.12)

[4] Pourquoi le Sud, voir aussi mon blog “

Le cas du Rituel de la Porte du Sud de Cakrasaṃvara” (2025)

[5] Lire à cet égard de Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Mind like Fire Unbound.

[6] Johannes Bronkhorst,

Aux origines de la philosophie indienne, 2008, Infolio, p. 60

[7] sGom gyi gnad gsal bar phye ba bsam gtan mig sgron, Volume 1, Page 42, Publisher: s.w. tashigangpa leh 1974 TBRC MW00EGS1016286

[8] Śivapurāṇa “26-27.

"Après m'avoir adoré ici même dans le liṅga, moi le Seigneur qui réside dans le liṅga,

La demeure dans le même monde (sālokya), la proximité (sāmīpya), la forme semblable (sārūpya), et la participation aux mêmes pouvoirs (sārṣṭi),

Ainsi que l'union (sāyujya) - ces cinq sont considérés comme les fruits des pratiques rituelles et autres.

Vous tous, vous obtiendrez rapidement tous vos désirs accomplis."

arcayitvā 'tra māmeva liṃge liṃginamīśvaram // ŚivP_1,9.26ab/

sālokyaṃ caiva sāmīpyaṃ sārūpyaṃ sārṣṭireva ca // ŚivP_1,9.26cd/

sāyujyamiti pañcaite kriyādīnāṃ phalaṃ matam // ŚivP_1,9.27ab/

sarvepi yūyaṃ sakalaṃ prāpsyathāśu manoratham // ŚivP_1,9.27cd/

Sālokya - partager le même monde que la divinité,

Sāmīpya - être proche de la divinité,

Sārūpya - avoir une forme semblable à la divinité,

Sārṣṭi - partager les pouvoirs divins,

Sāyujya - union complète avec la divinité.

[9] Voir

The Amanaska: King of All Yogas, A Critical Edition and Annotated Translation with a Monographic Introduction, Thèse de Jason Birch, Balliol College, University of Oxford, 2013.

[10] Les méthodes et la terminologie de l'

Amanaska sont largement dérivées du śaivisme tantrique. L'

Amanaska a eu une influence notable, étant l'une des sources de la très influente

Haṭhapradīpikā et ses versets se retrouvent dans d'autres textes de yoga médiévaux. Il a également été directement cité dans des recueils et ses terminologies ont été absorbées par certaines Upaniṣads de Yoga. Malgré cela, son auteur est inconnu, et l'attribution récente à Gorakṣanātha est considérée comme erronée par Jason Birch. Site

The Luminescent de Jason Birch.

[11] Terminus ad quem (date la plus tardive) : Le XIIe siècle. Ceci est basé sur l'utilisation extensive de versets de ce chapitre par Hemacandra dans son

Yogaśāstra, un ouvrage qui peut être daté avec certitude du XIIe siècle. Le fait que de nombreux versets parallèles soient regroupés de manière similaire dans les deux textes prouve que la majeure partie du deuxième chapitre de l'

Amanaska existait avant le XIIe siècle.

Terminus a quo (date la plus ancienne) : Le XIe siècle. Cette proposition est plus tentative et repose principalement sur l'absence de certaines terminologies du deuxième chapitre dans les textes composés avant cette période, ainsi que sur les similarités avec des œuvres de cette époque, telles que le

Kulārṇavatantra, l'

Amaraughaprabodha et le

Candrāvalokana.

Le deuxième chapitre est considéré comme l'un des plus anciens textes de yoga à enseigner un type de yoga appelé Rājayoga.

Ce deuxième chapitre a été composé entre le XIe et le XIIe siècle. Le premier chapitre a été composé entre la fin du XVe et la fin du XVIe siècle. La recension nord-indienne qui combine les deux chapitres est datée entre la fin du XVe et le XVIIe siècle.

[12] Contempler un ciel sans nuage pour induire un engourdissement et une immobilité, menant à la révélation du Soi. Regarder une portion d'espace "tachetée" par le rayonnement du soleil ou d'une lampe, afin que "l’essence de son propre Soi" resplendisse. Ou encore, fixer une "tache ou fulgurance (

äbha) sombre" en fermant les yeux, puis les ouvrir subitement pour ne voir que cette tache, menant à l'absorption dans la "Beauté du Dieu" (

ābha,

vapus).

[13] Le Vijñana Bhairava, Texte traduit et commenté, 1961, Collège de France

[14] ity uktam etat sahajāmanaskaṃ śiṣyaprabodhāya śivena sākṣāt | nityaṃ tu tan niṣkalaniṣprapañcaṃ vācām avācyaṃ svayam eva vedyam || 91 ||

“This natural, no-mind [state] has been taught thus [to Vāmadeva] directly by Śiva [him-self] for the awakening of his disciples. However, [the no-mind state] is eternal, aspectless, undifferentiated, not expressible by speech and can only be experienced by oneself alone.”

citte calati saṃsāro 'cale mokṣaḥ prajāyate | tasmāc cittaṃ sthirīkuryād audāsīnyaparāyaṇaḥ || 92 ||

"When the mind is moving, the cycle of rebirth [prevails]. When [the mind] is not moving, liberation arises. Therefore, [the yogin] makes his mind steady; he is devoted to [the practice of complete] detachment.” (Birch, 2013)

[15] oṃkārais trividhair vicitrakaraṇaiḥ prāpyaś ca vāyor jayas

tejaścintanam antarālakamale śūnyāmbarālambanam |

tyaktvā sarvam idaṃ kalevaragataṃ matvā manovibhramaṃ

dehātītam avācyam ekam amanaskatvaṃ budhaiḥ sevyatāṃ || 108 ||

“The conquest of the breath can be achieved by means of [reciting] the three types of Om and by various [haṭhayogic] Mudrās, as well as meditation on a fiery light [or meditation] on a supporting object [like] the empty sky [which are done] in the lotus of the inner space [of the heart].123 [However,] having abandoned all this [because it is] situated in the body [and therefore limited], and having thought it to be a delusion of the mind, the wise should practise the no-mind state, which is unique, beyond the body and indescribable.” (Birch, 2013)